About Last Friday’s Internet Outage

On Friday, October 21, 2016, some of the world’s most popular websites and many many others became inaccessible. The cause of this outage was a DDoS (distributed denial of service) attack on Dyn, a provider of DNS services. In this post, I’ll explain what that last sentence means. I’ll also share senior PINT staff’s answers to some important questions you may have as a result of the outage.

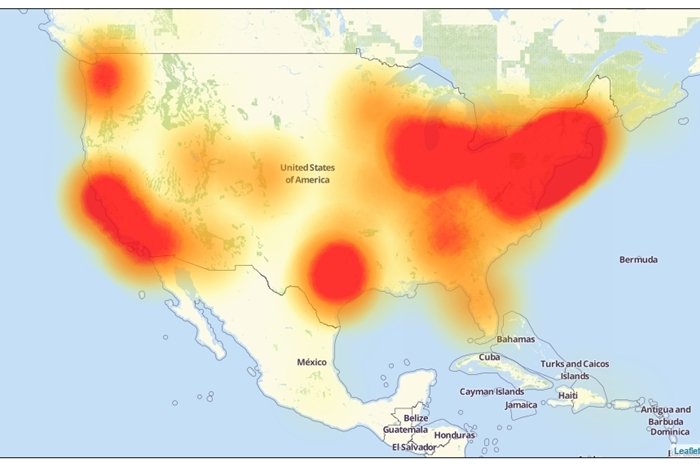

Source: Level 3

So, What Exactly Happened?

Someone targeted Dyn with a DDoS attack. Let’s break that down:

Someone

Although security experts in government and industry are still investigating, no one is yet sure who was behind the attack. There are some theories based on the size of the attack & other factors. None are confirmed.

DDoS

DDoS stands for distributed denial of service. These attacks have been seen before. During these attacks, attackers try to make a service unavailable by inundating it with requests.

Dyn

Dyn is one of the largest providers of DNS (domain name services). DNS is the service that translates the names of websites and other Internet-based services into numbered IP addresses. Here’s how it works:

Without DNS, most Internet-based programs (including but not limited to your browser) simply fail, because they stop being able to find any online services (such as your website, or your mail server) by name, and therefore they stop communicating with those services.

So: Dyn’s system was overwhelmed with traffic and as a result they could not complete any requests. All of the domain names Dyn’s service is responsible for translating, became useless: like a list of place names that no longer point to any specific location on a map.

According to Tech Republic, the result was:

“The world’s biggest websites—Twitter, Netflix, Airbnb, Reddit—became inaccessible to millions of internet users. Maps of the outage showed vast blooms of red in the upper Midwest, the Northeast, Texas, Washington, and California, reflecting the areas that had been hit hardest.”

How is This Attack Different?

Previous DDoS attacks differed in two major ways:

- Target

- Scale

In the past, DDoS attacks have tended to target individual sites. But Friday’s incident was an attack on the Internet itself, because DNS is a service that all sites and other services rely on.

Past incidents were also carried out by networks of compromised computer systems (such as servers or workstations) running scripts at a coordinated time–so called botnets. Friday’s attack also came from a botnet, but this one utilized software called Mirai. This is malware that infects not full blown computer systems but rather devices connected to the Internet of Things (IoT). Think security cameras, DVRs, and routers that connect to the web but for which many of us never change default passwords (or whose passwords may even be hardcoded in the firmware, and thus not changeable by users at all).

Being able to build a botnet out of millions of unsecured consumer IoT devices turns out to be shockingly easy. The source code to do it has even been publicly released. This greatly expands the number of nodes available for the attack, making detection and countermeasures much harder.

What is also alarming about the scale of Friday’s incident is that it had such an effect, despite only using ten percent of Marai’s nodes.

More Questions for PINT’s Experts

If this type of attack is so powerful, why haven’t we seen it before?

These attacks actually have happened before, just not on this scale. Security researcher Brian Krebs was hit with a similar (but smaller) attack just last month.

Can you ever control it?

Not really: this is an attack on the internet at a fundamental level. Most of what can be done is already in place. Efforts to detect and drop the superfluous traffic before it overloads sensitive systems is already being done at the level of ISPs and other core service providers like Dyn itself. There’s not much you or we can add to that effort.

However, there are things you can do if an incident like this occurs to maintain user access to your site. The main tactic sites used on Friday was to point their domain name records to a different set of name servers for resolution. For example, PINT moved some sites from Dyn to Cloudflare to restore availability.

However, switching services is not instantaneous. It depends on the TTL (time to live) for a site’s DNS settings. TTL is a rule for how long the records can be cached once they are requested. Depending on the site, this could take up to 24 hours.

Costs: Money, Performance, and Time

Of course, DNS records can use a shorter TTL, say about five minutes. But that comes with a cost in dollars. DNS services charge by the number of DNS resolutions, which increase with shorter TTLs.

There is also the potential for performance costs, too. Doing fresh DNS lookups takes time versus caching the results.

Also, making the switch to another DNS provider still requires exporting your zone file (DNS records) from one service and importing it into a new one.

Do you really want to avoid the performance hit and emergency change management issues? You could preemptively configure your DNS records to use multiple DNS providers simultaneously, giving them a priority so that when one service is unavailable DNS requests can be provided instead by your secondary service. But in order to do this, you’ll have to maintain a commercial relationship with both DNS service providers. Or several providers, if you’re really paranoid.

This too will come with a financial cost, as well as the burden of keeping your zone files in sync as you make changes.

Will these attacks ever stop?

DDoS attacks on DNS providers (Dyn or others) may happen again. The Internet relies on DNS services being available–if they were to respond to an attack by simply going offline temporarily, that would achieve exactly what the attacker wants. DNS services have no choice but to try to stay “up.” But as we saw on Friday, that is very difficult to do when there are so many unsecured devices in the wild, that can be mobilized for an attack.

Defeating such attacks is really a vast technical challenge for DNS service providers, ISPs, security researchers, and even government agencies. And it’s not only a technical challenge: the ultimate solution will almost certainly require stepped up regulation and enforcement of information security standards across the full range of connected devices. Hopefully the botnets of the future become much harder to assemble and control, at least at the huge scale we saw demonstrated on Friday.

Big thanks to Joe Lima for his input on this post.